For years I have used the Duluth Power and Control Wheel to understand and teach domestic violence prevention. I have also used the Equality Wheel from the National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence to help men learn alternatives to destructive power and control in relationships. In this article I combined the two and discuss them in an effort to explain how to reduce intimate partner violence and improve relationships.

What is Power?

Everyone wants influence over other people. In relationships perceptions of power are critical to understand. We do not have the option of not using power. We only have options to use power destructively or productively. Exercising influence or control is one of the basic human needs. The ability to meaningfully influence important events and people around us is necessary for our a sense of well-being and personal effectiveness. Exercising personal power is crucial to how you feel about yourself. High power is often a goal that people strive for. Without some sense of agency in your interpersonal relationships, you would soon feel worthless as a person.

In interpersonal relationships power is a property of the social relationship rather than a quality of the individual. Your dependence on another person is predicated on the importance of the goals the other can influence. If there are other avenues available to accomplish your goals, you will be less dependent on another person. If you want more power, it becomes important to increase the other person’s dependency on you. One way to reduce power others have over you is to change your goals or what you want from them.

It’s easy to confuse conversational control with power; they are not the same thing. One person may dominate the conversation, but if you refuse to cooperate, their power is nullified. People who look the most powerful to outsiders are often less powerful than they appear. You can’t tell from looking without examining the dynamics of the relationship.

Often during conflicts each person firmly believes that the other person has more power. Many problems result in this situation because the image people have of their power (and others) is unrealistic. Conflicts escalate if you or the other person believes you are in the low-power position.

Power Denial

When people view power as negative they may deny that they have power.

“I'm not myself when I drink.”

“I can't help it. I told you I had a temper.”

“I did not say that.”

“I forgot I said that.”

“People are always bothering me too much! Oh, I'm not talking about you…”

“I'm used to being treated unfairly by others…”

Everyone has some power.

Power Currencies:

Power currencies are basically things that people find valuable to use in relationships to garner influence, status, and power. Here’s a partial list:

Reward, coercion, expertise, threats, promises, persuasion, reinforcement control, information control, exploitation, manipulation, competition, special skills and abilities, personal attractiveness, likeability, control over rewards/or punishments, rank, persuasion, control, surrender.

People try to spend currency that is not valued in a particular relationship and, when they do, problems arise. Power depends on having currencies that other people need. Once a relationship deteriorates, power concerns increase.

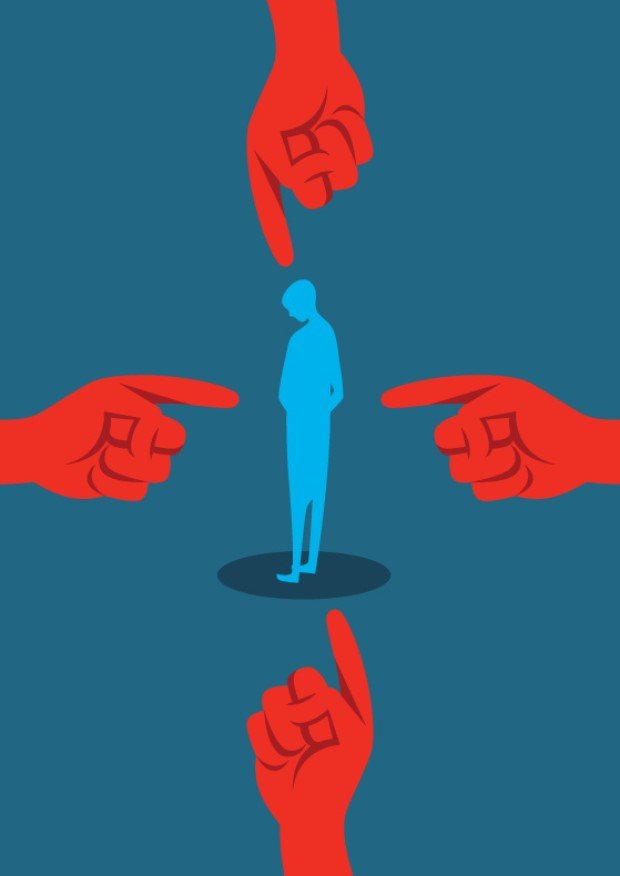

Destructive power vs. constructive power

Destructive Power:

Destructive power is power used over or against someone. Its effectiveness derives from competition and dominance. Long-term it is destructive to the relationship, ultimately leading to relationship termination. What follows are examples of destructive power currencies from the Power and Control Wheel:

Intimidation: Merriam-Webster: to make timid or fearful: Frighten; especially: to compel or deter by or as if by threats.

Making your relationship partner afraid by using looks, actions, and gestures. Smashing things. Destroying her property. Abusing pets. Displaying weapons.

Many of us grew up in households with parents who practiced corporal punishment. “Do I need to give you something to cry about? Or Do I need to fix your face? Were common refrains heard in my household throughout my childhood. They were effective because the threat of getting an ass whipping always loomed in the background whenever my father disciplined me during my childhood. That's intimidation.

Emotional Abuse: Emotional abuse is an attempt to control, in just the same way that physical abuse is an attempt to control another person. The only difference is that the emotional abuser does not use physical hitting, kicking, pinching, grabbing, pushing or other physical forms of harm. Rather the perpetrator of emotional abuse uses emotion as his/her weapon of choice.

Putting her down. Making her feel bad about herself. Calling her names. Making her think she’s crazy. Playing mind games. Humiliating her. Making her feel guilty. Here are some examples: “You didn't do that right. What's wrong with you? You're always nagging me I just go home from work. I don't want to hear that right now.”

Isolation: Humans are hardwired to interact with others, especially during times of stress. When we go through a trying ordeal alone, a lack of emotional support and friendship can increase our anxiety and hinder our coping ability.

Controlling what she does, who she sees and talks to, what she reads, and where she goes. Limiting her outside involvement. Using jealousy to justify actions. “I don't like your friend Sandra. She always has something to say about our relationship. I really don't like you talking to her. I don't want you to invite her over here. I don't like her.”

Minimization, Denial, Blame: Minimizing means downplaying the severity and effects of one's abusive behavior: Denying means pretending the abuse never happened: Blaming means making someone else responsible for your abusive behavior:

Making light of the abuse and not taking her concerns about it seriously. Saying the abuse didn’t happen. Shifting responsibility for abusive behavior. Saying she caused it. “That's no big deal. Why are you still on that? If you hadn't got in my business, I would not have had to put my hands on you. You know how my temper is.”

Using Children: Making her feel guilty about the children. Using the children to relay messages. Using visitation to harass her. Threatening to take the children away.

“Is your mother seeing anyone? Are there any men coming to the house?”

Economic Abuse: Preventing her from getting or keeping a job. Making her ask for money. Giving her an allowance. Taking her money. Not letting her know about or have access to family income.

“I started working under the table so I could avoid child support.” That's a common statement I hear men make who don't understand economic abuse. Also living with a woman and waiting on her check—money that is not theirs—each month.

Male Privilege: Treating her like a servant; making all the big decisions. Acting like the “master of the castle,” being the one to define men’s and women’s roles. Leaving the house whenever they want, thereby shirking household responsibilities such as chores and childcare, leaving their partners to pick up the slack. Squandering the household income on vice.

Coercion and Threats: Making and/or carrying out threats to do something to hurt her. Threatening to leave her, to commit suicide, or to report her to welfare. Making her drop charges against you. Making her do illegal things. Similar to intimidation, threatening to leave the relationship if certain conditions are not met. Threatening violence when upset in an effort to get their own way.

Power sickness

Power sickness resides at both ends of the power spectrum. People with high power can begin to abuse the people around them who they perceive have less power than them. And people in power down positions can begin to resist more forcefully leading to acts of violence and terrorism. In severe, ongoing conflicts both parties perceive that they have low power, and they continually make moves to increase their power at the other’s expense. This can make each person feel justified to use dirty tricks. Lower-power parties will sometimes destroy a relationship as the ultimate move to rebalance power. The more you struggle against someone the less power you will have over them.

Constructive Power: